Rhyolite Ghost Town

This Wild West gold boomtown sprung to life after a couple of prospectors discovered high-grade, extremely valuable gold ore in 1905. Several mining camps, including Rhyolite, popped up in the region, which later became known as the Bullfrog Mining District. But why a name like Bullfrog, in the middle of an arid desert? The two prospectors who discovered gold in the area—Frank “Shorty” Harris and Ernest “Ed” Cross—decided that the rock found throughout the region looked greenish, and was spotted with big chunks of yellow metal, resembling the back of a bullfrog.

As one of the most photographed ghost towns in the West, make Rhyolite Ghost Town part of your Free-Range Art Highway discoveries.

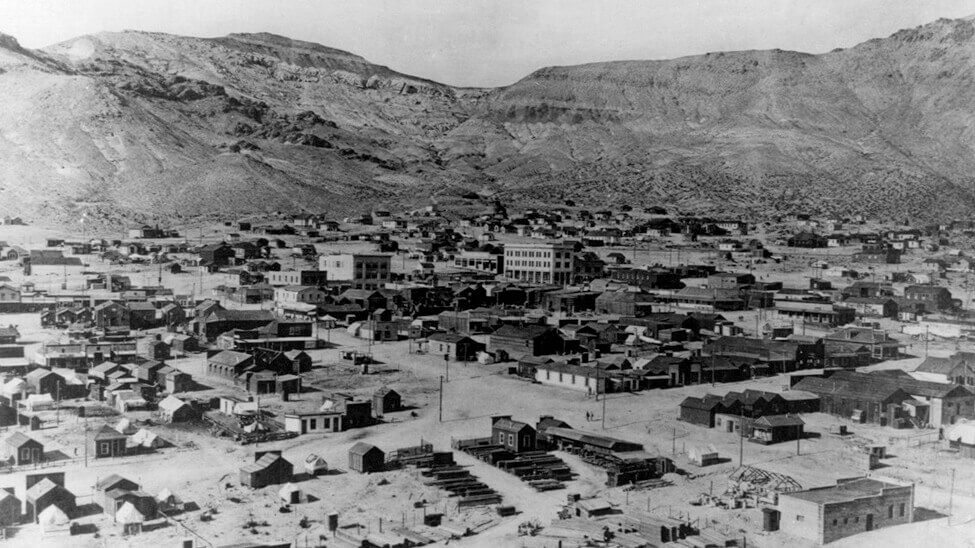

While mining camps were very common in Nevada during the late 1800s and early 1900s, Rhyolite stood out because of the tremendous value tethered to the ore samples. The traces of gold found in ore coming from the Bullfrog-area mines were known to bring in a stunning $16k dollars per ton…which translates to about $450k in modern standards. Word of this wildly lucrative operation spread all the way north to Goldfield and Tonopah, and what originally started as a two-tent mining camp soon boomed to an estimated 5,000 people within six short months.

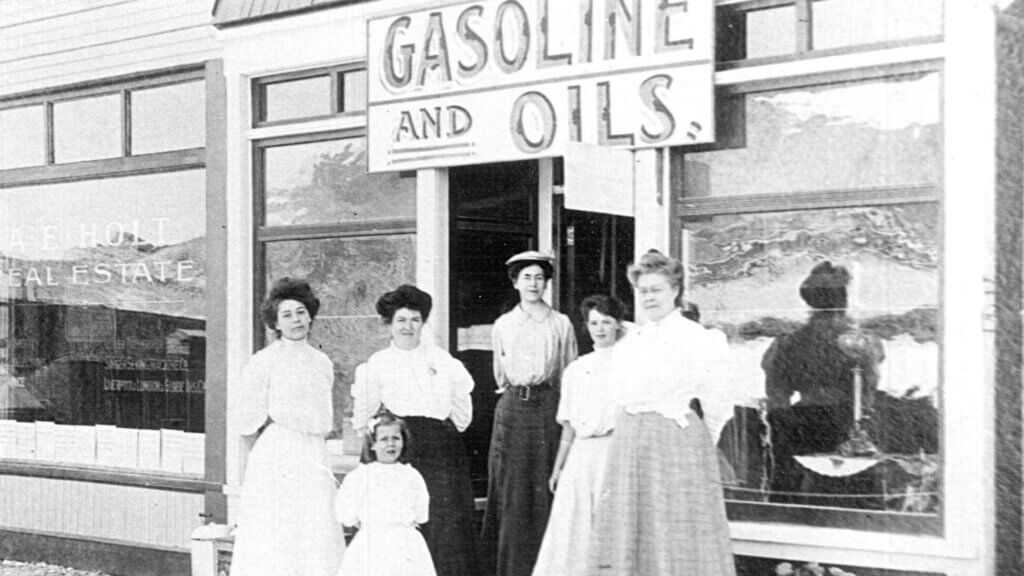

As if Rhyolite sprung to life overnight, this community quickly became the epicenter of the Bullfrog Mining District and aside from a swelling population, boasted 50 saloons, 35 gambling tables, 19 lodging houses, 16 restaurants, several barbers, a public bath house, and the Rhyolite Herald—a weekly newspaper publication. To add to an already growing population, a hard-to-imagine four daily stagecoaches connected “The World’s Greatest Gold Camp” to Rhyolite, ushering in a steady flow of people to Nevada’s newest gold discovery.

Rhyolite had gained such tremendous success that it soon caught the attention of steel magnate and savvy businessmen Charles M. Schwab. By 1906, Schwab had very seriously invested in what was happening in Rhyolite by purchasing the Bullfrog Mining District, which elevated the operation from good to grand. Thanks to Schwab, Rhyolite soon had the most decadent features of any boomtown in the region, with the implementation of electricity, indoor plumbing, and a contract with the Las Vegas and Tonopah Railroad to run a spur line to the area. Before long, three railroads were serving Rhyolite, and just one year later, the Tonopah and Tidewater Railroad (RRT) began service to Rhyolite as well.

Thanks to Schwab, people living in Rhyolite lived life in grandeur by 1907, with concrete sidewalks, electric lights, water mains, telephone and telegraph lines, daily and weekly newspapers, a monthly magazine, police and fire departments, a hospital, school, train station and railway depot, three banks, a stock exchange, an opera house, a public swimming pool, and two churches.

Rhyolite’s Bust

While Rhyolite and the Bullfrog Mining District produced more than $1 million within three short years [about $27 million by today’s standards], this boomtown declined almost as rapidly as it came to life. Like most other has-been mining communities, the high-grade ore began to diminish and the 1906 San Francisco earthquake proved to be the kiss of death as the rail service was seriously disrupted. By 1910, mines began to close, businesses failed, and workers sought employment elsewhere. The banks, newspapers, post office, and train depot closed by 1914, and the power companies shut down the electricity powering Rhyolite in 1914, essentially forcing all remaining residents out of town. Within just one short year, the entire town was almost completely abandoned, and by 1920 only 14 people called Rhyolite home.

As timber was a hot commodity during this time, many of the town’s remaining infrastructure was relocated to other towns and mining camps. If portions of the buildings were not relocated, then entire buildings themselves were moved. The Miner’s Union Hall in Rhyolite became the Old Town Hall in Beatty, many of the buildings were used to construct the school in Beatty, and one of Rhyolite’s original saloon countertops was even relocated to Goodsprings and has been a fixture in the Pioneer Saloon since 1913.

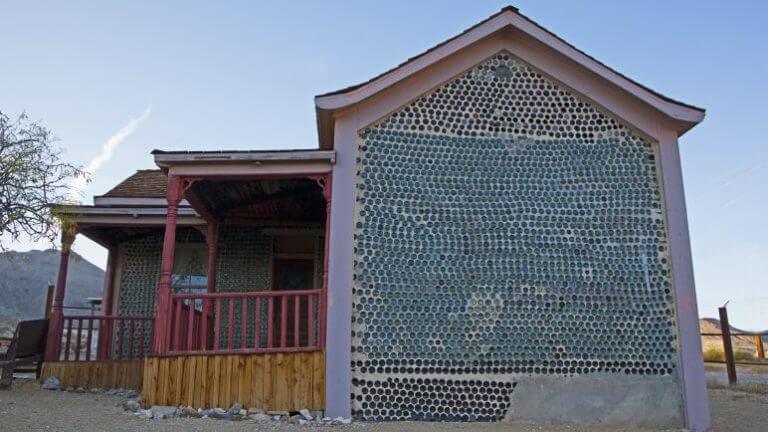

Tom Kelly Bottle House and the Goldwell Open Air Museum

Though the lights went out in 1914, they turned back on a decade later, when Paramount Pictures used Rhyolite as a setting for the film The Air Mail. With countless opportunities for drinking in true American West scenes and connecting with another time, perhaps the most pristine is the Tom Kelly bottle house, built completely out of 50,000 medicine, beer and whisky bottles. Restored for a Paramount Pictures film in 1926, the house still stands today and is the oldest and largest known bottle house in the United States.

Aside from being featured on the Silver Screen, tourism soon began to flourish in nearby Death Valley National Park and Rhyolite saw a wave of visitors during the 1930s. A few souvenir shops opened, and by 1984 Belgian artist Albert Szukalski created his rendition of The Last Supper sculpture. Today, this outdoor sculpture garden is known as the Goldwell Open Air Museum, on the southern entrance to the ghost town.

Hours:

Rhyolite Ghost Town is open and welcomes visitors from sunrise to sunset, seven days a week.

Admission:

Rhyolite Ghost Town and the Tom Kelly Bottle House are managed by Nevada BLM, making free public access available to all.

This Location:

City

BeattyRegion

Central